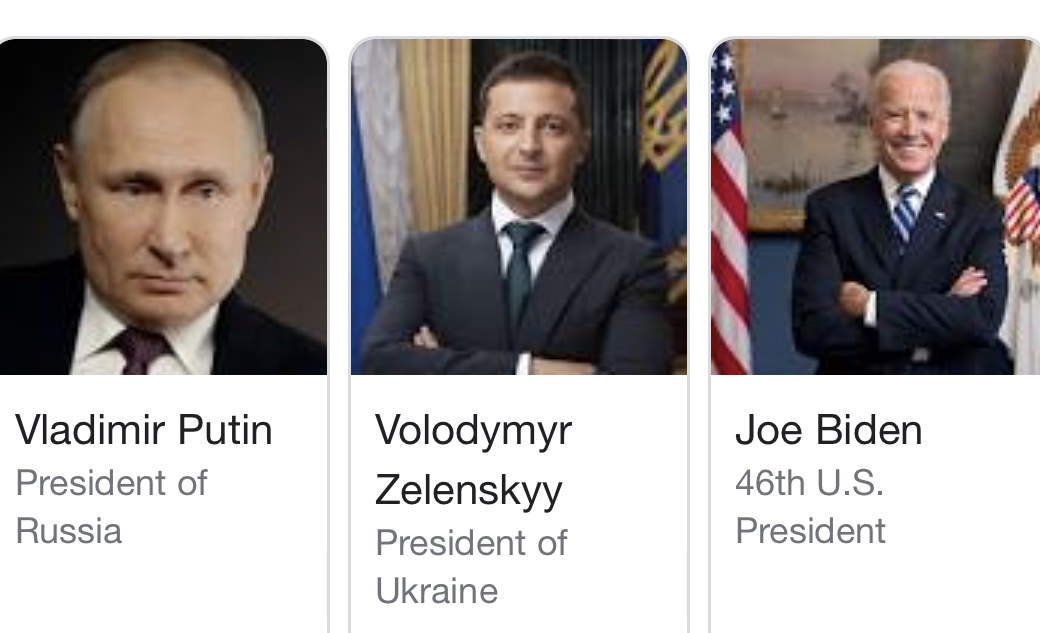

How to Talk to Children About the War in Ukraine

Posted March 17, 2022 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Counseling parents and children during the Covid epidemic has been emotional and draining. I am afraid that the war in Ukraine may break our strength and fortitude.

The horrific images coming of children being pulled from their father’s arms as they leave to fight, buildings blown to pieces, or the unimaginable photographs of elderly couples struggling to walk with their canes and few possessions are mesmerizing. The heart wrenching image of a small child walking alone in a street crying loudly — I have been overcome, and I continue to struggle to find my grounding in a world that seems to be repeating the atrocities of World War II.

I know I am not alone in this feeling as I search for familiar faces in the images flashing on my TV screen. I am a second-generation American Jew. My grandfather left Russia before World War II. Samuel Kislin left behind eight brothers, parents, and extended family he never saw again. He was only 16 when he arrived at Ellis Island. He was one of the lucky ones. I am one of the fortunate ones. Sharing my story helps make me feel connected in the moment, to remember that I have the luxury of being safe while stirring memories of incredible endurance of the human spirit.

We are all connected. We all have a shared responsibility to take care of one another. These are the mantras playing over and over in my mind.

How do I help the people of Ukraine? How do I help you, the loving mothers and fathers, grandparents, teachers, and mental health professionals who are struggling right here with me? Some parents have shared that they don’t think their children are “paying attention” to the war. I kindly disagree. I believe with that children are really struggling right now, whether they are viewing graphic photos of bombed-out buildings or blown-up bodies in the streets.

I know this to be true from the clients, friends, and family, but I also know this from the research on trauma, both mine and others’.

The long past two years have eroded much of the fabric that binds children’s sense of belonging, self-worth, and, most of all, resilience.

A war of this magnitude playing out in real time is new for many children. The constant bombardment and images of death fill their social media feeds, prompting thoughts and feelings that are too much for many of them.

But you can help. You must push through your own emotions and fears and be there for your kids.

- Start with you. Breathe. Acknowledge that these are difficult times for parents and children. Limit the amount of time you spend on social media or watching the news. And don’t assume your child is not seeing horrific images on the TV or other electronic devices.

- Monitor not only where your child is hanging out on their devices but for how long. Sit down with them in a calm manner and talk about how you are upset by the reporting of the war. Ask open ended questions: “What are you seeing?” “What are you hearing?” “What are your thoughts?”

- Don’t assume your child doesn’t want to talk. They may just grunt or shrug their shoulders. This is hard for them. Be their guide. “I don’t really know that much about the history of Ukraine, do you? Let’s do some research.”

- Be honest, and direct. Don’t lecture, freak out, or overshare. “This is a horrific episode that is unfolding before our eyes. There are things we don’t know: We don’t how long this will last and what effect it will have on many people.”

- Volunteer. Focus on things you can control and enlist your child. “Let’s think of ways we can help.” For example, reach out to a local Ukrainian church and ask how you can help. Children are incredibly imaginative and creative. Ask them, and then listen.

- Structure and boundaries help children feel safe. Now is a great time to review your bedtime rituals such as no devices in the bedroom after a set time.

- Get moving. Go into nature. There is extensive research supporting the idea that exercise, proper sleep, good nutrition, and time in nature substantially help one’s mood. Make plans for activities that you can control: “Let’s plan next week’s meals.” “Let’s go on a nature walk.” “Let’s see if anyone in the neighborhood wants to join us in going on a hike, bike ride, or scavenger hunt.”

- Remember to partner with your child. You can do this by monitoring your own behavior. What is triggering you? If you feel triggered, walk away; literally take a time out, and rejoin your child when you can use a calm tone of voice and are able to control your emotions, especially anger.

Children need to feel secure to develop into self-confident, kind, productive, socially conscious adults. This doesn’t happen by accident or by only focusing on their productivityor grades. Celebrate moments in your child’s life — cuddling up with a young child or sitting across the table from a teen without electronic devices. Look them in the eyes and smile. Convey to them that you see them. Acknowledge that this is a scary time, but that they are not alone, and you will navigate this together.

Comments by inspireamind1

Private: I Am Not A Prescriber ( Common Medications & Uses)

Medications and their uses. I am not a prescriber.. but ...

Products That Assist Us In Calming From Within

Calmigo Weighted Blankets calming down teens adults without medication relaxation ...